After seeing yet another post from someone whose therapist told them that “DID is a diagnosis that we have come to doubt as therapists…”, predictably, I once again got upset. I responded directly to the post because such a statement is offensive, demeaning and wrong. It will undermine DID patients and produce no benefit.

Knowing that this is a long uphill battle of educating therapists as well as supporting those with DID, I feel compelled to revisit some key points I have been making in my books and blog since 2014. Although it is now about 15 years since I retired from practicing psychiatry, I remain unable to let go of my interest in the treatment (and mis-treatment) of trauma and dissociation. I continue to do what I can to promote the healing of those who suffer from DID.

I find that there remains a good deal of misunderstanding on DID in the general public and, most unfortunately, among professionals in the mental health field. What continues to disturb me is the number of individuals continuing to post messages about their difficulty in locating qualified therapists to help them. This is a sign of our ongoing professional failure to support those suffering from DID.

This is a denial both about the depth and extent of early childhood trauma as well as its impact later in life. It seems to have resulted in a lack of confidence on the part of many therapists which prevents them from treating individuals with DID. It is as if they are frightened of identifying clinical presentations of DID. I am not sure why this is the case, unless they would place themselves in danger should they either diagnose or treat someone with DID.

Many authors of psychology textbooks state that DID is rare. But they don’t even argue their case, they just make the flat statement without citing anything that would contradict the studies that show DID is not so rare. Simply because an otherwise experienced psychiatrist near the end of his career says that he has never seen one such case doesn’t change the statistics. In fact, DID is often simply misdiagnosed as depression, panic attack, borderline personality and bipolar disorders. Relying on a history of misdiagnoses fails to prevent the perpetuation of that ignorance to the next generation of therapists.

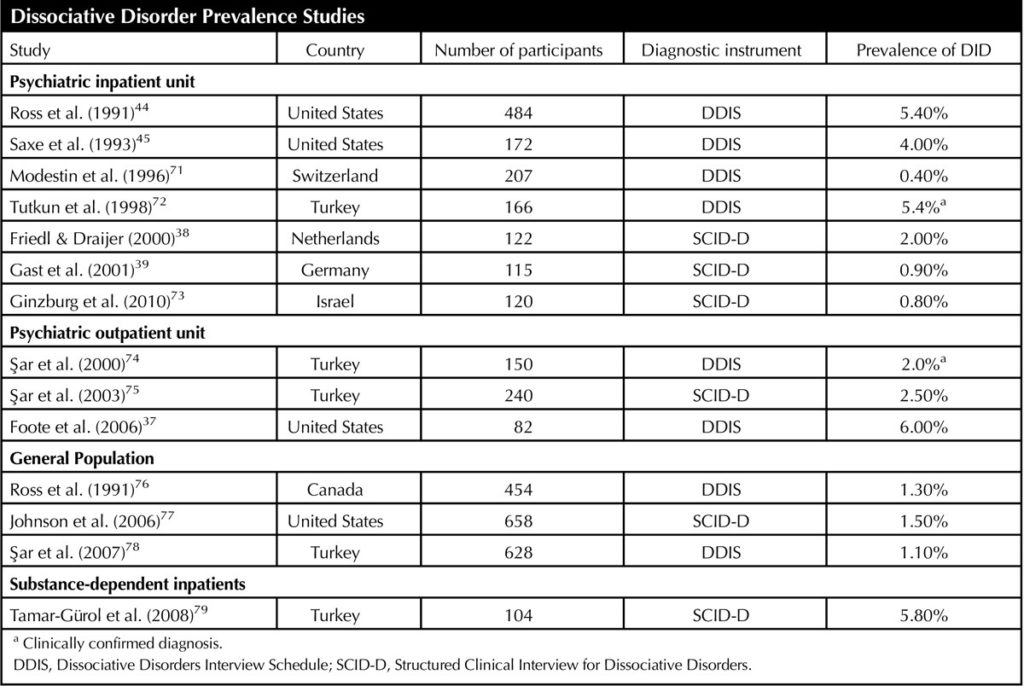

[1] DID Prevalence

The prevalence rates found in psychiatric inpatients, psychiatric outpatients, the general population, and a specialized inpatient unit for substance dependence suggest otherwise. DID is found in approximately 1%–5% of representative community samples. Using a questionairre method for measurement in a representative sample of 658 individuals from New York State, 1.5% met criteria for DID when assessed with SCID-D questions. Similarly, a large study of community women in Turkey (n = 628) found 1.1% of the women had DID .

I am not sure if there is really a “normal’ person who has never experienced dissociation. Dissociation occurs over a wide spectrum from normal individuals to those with full blown DID. As I have said before, dissociation is something we are familiar with because it occurs in all of us. For example, when you are driving a long stretch of freeway listening to your favorite music, your attention is definitely not 100% on the road and you may easily be unable to remember having passed by this or that town.

Consider whether you know anyone that has never had conflicts with members of their family, or gotten angry at a driver who cut them off? Would you feel comfortable being operated on by a surgeon who is distracted, even marginally, by such thoughts? I certainly would feel extremely nervous if a neurosurgeon operating on me was incapable of some degree of dissociation.

[2] Obsession with Alters

Many people are obsessed with alters because one can only have a single citizenship card from a particular country, a single driver’s license from a particular Province or State, and a single social insurance number. This logic is then used to define “healthy” as meaning that we cannot behave or feel like we hold different identities. This misses the point and sends both therapist and patient in the wrong direction.

I think we need to review and revise the intensity of the focus on multiplicity in DID.

Perhaps it would help psychiatrists, psychologists and patients see the therapeutic path forward more clearly if they shift the emphasis from treating multiplicity as the disorder to treating the trauma and dissociation that manifests in multiplicity. The alters are not the problem. The problem is the internal conflict that untreated trauma generates.

When I was still practicing psychiatry, Multiple Personality Disorder as the diagnostic label made more sense than Dissociative Identity Disorder to my patients. It was more helpful because they experienced the different parts as different personalities in the common understanding of the term “personality.” Because they had more than one part, usually many more, calling it a “Multiple Personality” disorder acknowledged their internal experience whereas Dissociative Identity Disorder seems more geared to how they would be viewed by a therapist.

This approach of tying the label to the therapists’ outside view gives an undue weight to the presumption that mental health is restricted to the idea of a single ego structure that others experience as relatively consistent. To tell one of these alters that they were not real and only an expression of dissociation was not only unhelpful but ran the risk of undermining the necessary therapeutic alliance.

Again, I urge therapists not to miss the forest – the early trauma and its ongoing impacts – for the trees – the personalities/identities/alters/parts. Missing that forest will make genuine successful treatment difficult, if not impossible. Engaging alters without obsessing about them will enable you to treat the DID and help the patient heal from their trauma while limiting risk of re-traumatization.